Saturday 5th October, 2024 – Thurso, Ulbster, Lybster, Wick, Duncansby Head, Dunnet Head

Distance driven: 68.0 miles

Time at the wheel: 1 hour 36 minutes

Heiland coos spotted: 0 (Seriously? Are they hiding from us?)

Saturday morning saw a latish start, partly down to my insistence on completing Thurso parkrun while I had the opportunity, what with it also being parkrun’s 20th birthday and thus something very much worth celebrating. And a lovely flat course it is too, around the boating lake, then three laps between two bridges over the River Thurso. The volunteers were all very friendly, and there was fudge at the finish line too. That over with I went back to the apartment to get cleaned up so we could go out and try and cover the section of North Coast 500 we’d missed the day before.

That meant heading back to Ulbster which was just north of where we’d left the route the day before. Once back on the route we did a bit of back and forth as we tried to locate the parking so we could attempt to reach the Cairn o’Get. This is a chambered burial cairn set in “a landscape rich in prehistoric and later monuments”. Apparently, “the tomb and upright stones are still clearly visible in the landscape”. I’m not so sure about that because we gave up when the going started to get very boggy underfoot. Deciding we didn’t really have the footwear to tackle the route, we got back in the car and headed to Lybster.

In Lybster we hunted down the Waterlines Heritage Centre to see if it was open. There was rumour that it closed at the end of September but we were in luck and it was still open. We grabbed a quick lunch (potato soup) before going round the exhibits which are all about the 19th and early 20th century fishing industry in Lybster. This was a boom time for the town, with over 350 boats based there at one time. There are still fishing boats fishing along the coastline for lobster, crab, prawn, and fish, but the glory days are long gone when 50,000 barrels of herring a year were exported from Lybster. The statistics are mind-boggling when you hear that 1,500 fishermen, 100 coopers, and 700 gutters and packers were involved in the industry. For one thing you find yourself wondering where on earth they all came from – and the answer in many cases was from the Duke of Sutherland’s estates, and not willingly.

From Lybster we started heading north again, stopping off at the Castle of Old Wick, basically a ruined castle just outside the modern town. It took some getting to, and when we did arrive there were a number of notices announcing that it was closed “due to access restrictions in place as a precautionary measure while we undertake high level masonry inspections”. I’m guessing this means there’s a risk of bits of it falling off on a visitor’s head! You can still get very close so we made our way towards it, getting as close as we could. It’s a most mysterious structure in that there are a lot of stories about its history, but the archaeology is frustratingly incomplete, right down to the fact that the only wood that could be extracted turned out to be of a type which cannot be dated using dendrochronology. In fact “Bayesian analysis of the only two viable sub-samples provided a ‘wiggle match’ date of ca AD 1515–1550 (95% probability), with highest single-year probabilities in the range cal AD 1515–1535 (68% probability). The results represent the bark edge position and the felling date, or death date, of the timber. Careful consideration has been given to what the dating results mean. While our preferred interpretation is that the timber was used freshly cut, a rough notch at the better-preserved inner end could be evidence of re-use. The timber is clearly not part of a floor level and is seen as a fixture for an internal structure built either in or after the first half of the 16th century. The timber was much smaller than the masonry socket in which it sat, with a void behind it, and it may be that the socket is earlier than the timber and re-used for this fixture.” In addition, there are “no diagnostic architectural features” that could help with dating the structure.

The Old Man of Wick, as it is also known, is then possibly 14th century though it may be 12th century, and most likely not built by Earl Harald Maddadson in the 1100s, though who knows. The documentary evidence suggests the involvement of both the Sutherland and Oliphant families although there’s nothing before the 14th century, and it was definitely besieged during the Sutherland-Sinclair feud in the 16th century but beyond that not much is certain. The one thing you can say for certain is that it’s in a dramatic and imposing position on a 100 yard long narrow promontory, surrounded by 100 ft high cliffs.

We retraced our path along the cliff edge and headed into Wick itself. Wick gets a bit of a bad press in some of the guide books, but we actually quite liked it. Or at least the bits we saw. There’s a fine memorial statue out on the edge of one of the three harbours and there’s a great museum, the Wick Heritage Museum in Pulteneytown, which was the section of town developed to house the workers during the herring boom years. The museum is, naturally, big on the subject. It also contains the Johnston Collection, which is the archive that came from a local photographer’s business.

It covers the years 1863 through to 1975 and in its 50,000 or so images, seems to cover every aspect of life in Wick. They’re also very good photos of which over 40,000 are now online. It’s a terrific museum and deals with so much of what life was like for the herring fishers and their families.

From Wick we still needed to hit the top of the country and so, rather than bother with the tourist trap that is John O’Groats, we attempted to find a way to Duncansby Head and the sea stacks there. We couldn’t find a way through so instead we drove over to Dunnet Head and parked up there instead. The area is now an RSPB nature reserve, the most northerly point of mainland Britain being popular with puffins, razorbills, guillemots, fulmars, and kittiwakes. Sadly the puffins are only there in the summer and we were too late to see any.

It was now fiercely blowy out there, so after admiring the lighthouse (built in 1831 by Robert Stevenson) we decided we would retreat back to the AirBnB for an evening in eating beetroot and Parmesan pasta and getting ready to move on again the following day.

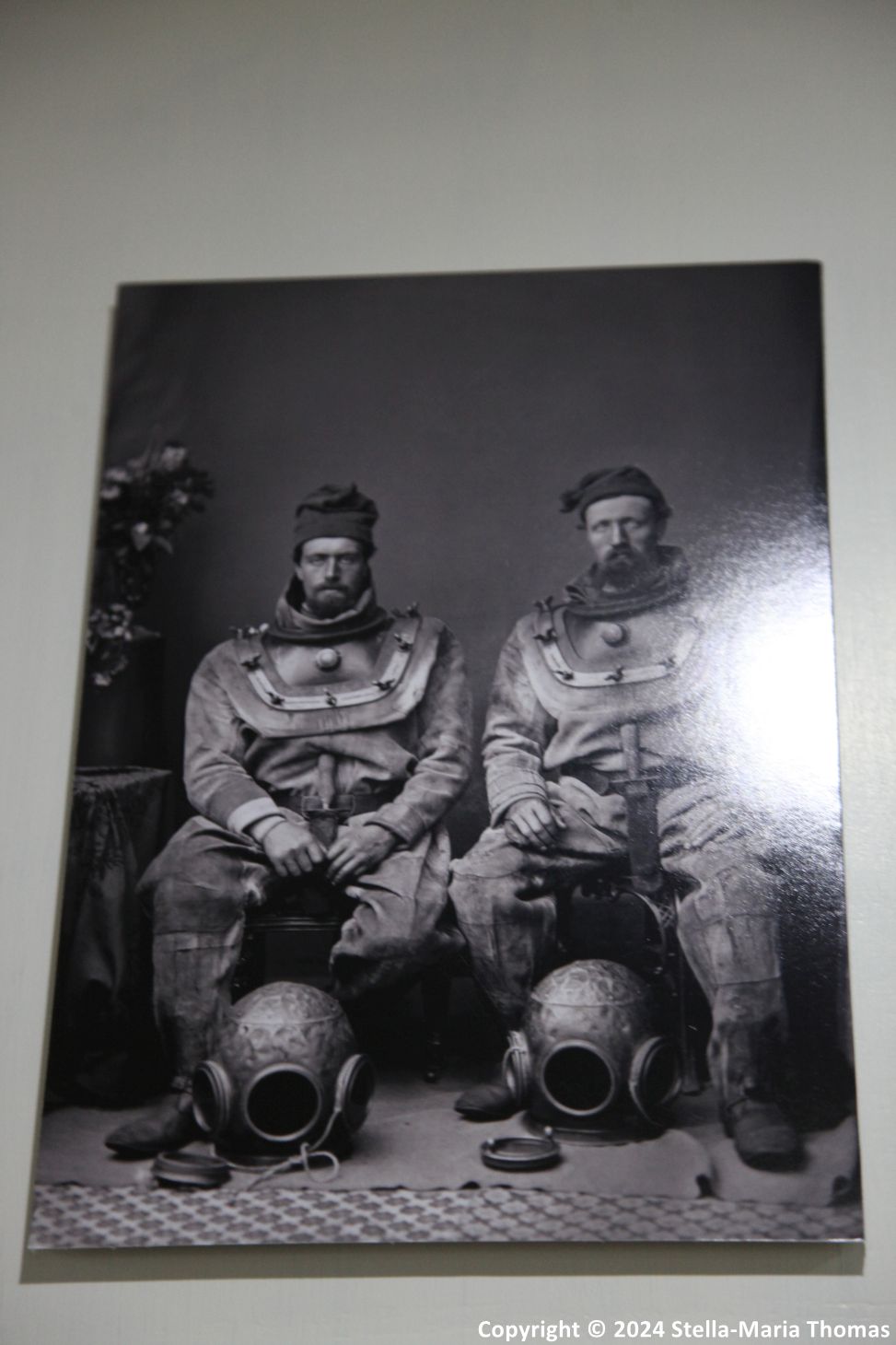

I like the picture of the divers. There is a diving suit just like it at the Immingham Museum close by where we live. Apparently, or so I am led to believe the suits were made in one piece and the diver had to wriggle in through the neckline. Looks impossible to me unless it was Houdini.

LikeLike

It was described elsewhere as a survival suit, though I think it was more that you survived being inside it than that it helped you survive.

LikeLike

Exactly so.

LikeLike